https://www.zerohedge.com/geopolitical/original-matrix-what-they-dont-teach-you-about-money

MD: Here at Money Delusions we’re well aware that they don’t teach you anything about money. And those of you who think you know… well, let’s see. We annotate this article.

The Original Matrix – What They Don’t Teach You About Money

by Tyler Durden

Sunday, Mar 02, 2025 – 08:20 AM

“You take the blue pill – the story ends, you wake up in your bed and believe whatever you want to believe. You take the red pill – you stay in Wonderland and I show you how deep the rabbit hole goes.”

– Morpheus, The Matrix

What is Money?

MD (MoneyDelusions): Watch how long he goes on before he tells you what money is. We’ll flag it when we see it. If you want to cut to the chase, read the right sidebar. You’ll know in less than 300 words

Some things in life are so deeply ingrained in our daily existence that we rarely stop to question them.

They are simply there, operating in the background, so fundamental to our existence that they feel as natural as the air we breathe.

We use them, rely on them, and move through the world assuming they are exactly as they should be.

For example, everyone is familiar with the phrase “Money makes the world go ‘round.”

This is rarely questioned and is rather accepted as self-evident.

Every day, you wake up, pay your bills, go to work, and check your bank account,—believing that you understand the system you operate within.

But have you ever stopped to ask yourself: What is money, really?

Not the textbook definition.

Not the economic theory you learned in school.

But the truth.

Money is everywhere. It dictates who eats and who starves, who rises and who falls. It builds empires and crushes civilizations.

It has fueled revolutions, financed wars, and controlled the fate of entire nations.

It is arguably the most powerful force on Earth, yet most people never stop to question its origins, its purpose, or its true nature.

You use money every single day. You earn it, you spend it, you save it. You trade your time and energy for it. It determines where you live, what you own, and the opportunities available to you.

It is so deeply embedded in your life that questioning it feels absurd—like questioning gravity or the air you breathe.

But have you ever wondered who decided what money is? Who, or what, gave it value? Or who controls it?

MD: Now that’s kind of provocative don’t you think? We’ll show that money stems directly from trade. Nobody “decided” it. It’s just obvious. Consider trade. There are 3 steps: (1) Negotiation; (2) Promise to Deliver; (3) Delivery. After the trade is agreed upon in step (1), if this is a Simple Barter Exchange (SBE), steps (2) and (3) happen simultaneously on the spot. One “object” is traded directly for another “object”. The most common object in every SBE is money in one of its forms. For trades spanning time and space, money facilitates steps (2) and (3). It may already exist and held by one of the traders or either trader may “create” it specifically for this trade. A good example is buying a car with 48 equal monthly payments. One trader makes the promise and creates the money. The other trader takes the money and his deal is done. But the trader creating the money has 48 more steps before he is done. Each month he brings (to the process) his 1-month’s payment; it is destroyed; and the remainder of his promise is reduced by that amount. It’s just that simple.

And more importantly—what if you have been playing a game where the rules were rigged before you were even born?

MD: And you know what? That’s exactly what you have been doing. And you know what else. You can stop it just as soon as you and your trading partners choose to stop it. The “real money process” (RMP) is in control. And it works because the money creation/destruction activity is never anonymous and is always totally transparent.

For those who are willing to look beyond the surface, the answers may be surprising.

But be warned: once you start asking the right questions, there is no turning back.

MD: Getting pretty exciting isn’t it!

Traditional Definitions of Money

Money is one of the most universally recognized yet least examined aspects of human civilization.

It influences every facet of our lives, dictating our economic opportunities, shaping global trade, and acting as a central force in ways few ever consider.

Yet, despite its ubiquity, money remains a concept that is deeply misunderstood.

MD: Including by the writer of this article. This is always such fun.

While we all use money, few of us ever stop to truly evaluate what it is, how it functions, and whether it works the way we assume it does.

The goal here is not to convince anyone of a specific perspective but to think critically about money—what it really represents and whether the reality matches what we have been taught.

MD: Your best clue is seeing where it is created and by whom. And your clue is seeing where it is destroyed and by whom.

If you were to stop someone on the street and ask them whether they knew what money was, they would almost certainly respond with a confident yes.

MD: Just as this guy might do… probably after he’s made you read all the way to the bottom… holding you in suspense. But we’ve tricked him. You already know the punch line. I think he’s paid by the word so let’s just try to sit back and relax..

However, if you pressed them further and asked them to give a proper definition, the response might not come quite as quickly. The initial certainty would likely give way to hesitation as they search for an answer.

Were you to push a little harder or direct the question toward someone well-versed in finance or economic theory, the answers would likely become more structured.

At this level, people might begin describing the attributes associated with a strong form of money—qualities that make it function effectively as a medium of exchange, store of value, and unit of account.

If the conversation were to then go even further, those thinking critically about the question might move past the attributes of money and instead focus on what money actually does.

They might start discussing its role in facilitating trade, its function in settling debts, or its importance in economic transactions.

Yet, even if all of these points are accepted as true, the core of the question still remains: What “IS” it?

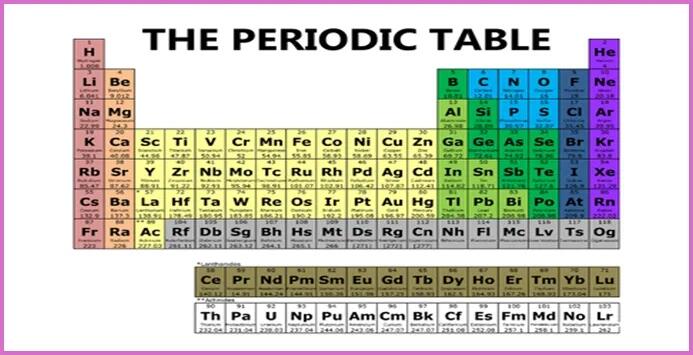

At its most fundamental level, a medium of exchange must be some “thing.” And what are tangible things made of?

MD: Ok. He still hasn’t told us what money is. Here’s a hint. Let’s see how long he goes before he tells you this: Money is provably “an in-process promise to complete a trade spanning time and space”. We’ll discuss its attributes as he moves along. No commodities are money. Commodities change value as their supply/demand balance changes. “Real” money doesn’t do that. “Real” money is a “process”. So right out of the box he’s getting it wrong… but maybe he’ll teach you some chemistry.

Commodities.

By this reasoning, money—when stripped to its most basic form—is a commodity.

And commodities are made up of elements found on the Periodic Table. However, not just any commodity (or any element) can serve as money.

MD: I guess he wasn’t aware that at the time USA became USA, tobacco leaves were used as money. Look below. Is it in the periodic table?

If a particular commodity is widely demanded and possesses some (or all) of the attributes that define strong money, then it ceases to be just a commodity and instead also transcends to become money itself.

At this point, it often becomes clear that money is the most marketable commodity, a good that serves as the final extinguisher of debt and that has been selected by free market forces over time.

MD: Tilt! Since money is a “promise”, the final extinguisher of debt is “delivery as promised”. It’s not selected by free market forces over time. It’s obvious from seeing it actually created by a trader like you and me. And it’s proven by that same trader as he completes his “delivery as promised”, and the money for the trade has been totally destroyed in the process.

This definition resonates with many who have studied the history of money and how different forms have evolved over time.

MD: You know what? We know of no instance of all time that a “real money process” has ever existed. We’ve had lots of stand-ins like precious metals, sea shells, big rocks with holes in them, and even IOU’s. Surprisingly, the IOU is the only thing that comes close to being money. But IOU’s only work between those two traders. Money is IOU between the creator and the RMP (Real Money Process). As he continues to distort we’ll slowly reinforce the truth and you’ll see clearly how it works.

Taking this concept a step further, and recognizing that money is a commodity, and commodities are made up of elements from the Periodic Table, one might even evaluate the various elements to see which of them has the most attributes which would allow it to “ascend” to become money.

MD: Wrong… money is not a commodity. And wrong… even all stand-ins are not in the Periodic Table. In fact, today only one is… Gold. That had a fight towards the end of the 19th century too as William Jennings Bryant claimed Silver was money (they’d just found a bunch in Nevada)… but the powers to be said it was not… and it thus was not.

And, as always happens, we want to stop him right here. He’s got it wrong. We can prove he’s got it wrong. We know with this false premise everything to follow will be wrong. Normally I’d advise you to quit reading and move on to the next article. But, though “time is money”, sometimes it’s worth the grind to follow along.

In doing so, one would realize that there in one commodity that has long been regarded as one of the strongest forms of money due to its unique set of attributes, which make it highly effective as a medium of exchange and store of value.

One of its most defining qualities is durability—unlike paper currency or other perishable goods, it does not corrode, tarnish, or degrade over time, ensuring that it retains its value across generations.

MD: Earth to whoever this is. Accounting records do not corrode, tarnish or degrade. And in a “real money process” where money perpetually maintains perfect supply/demand balance, it’s value never changes. No other exchange media cans claim that.

This durability allows it to function as a reliable form of wealth preservation, as it does not succumb to the forces of time or environmental conditions.

MD: But that’s not an issue. A promise has a fixed time and place it agrees to be delivered. Time is contracted. Environmental conditions are of no import whatever. We’re in a blizzard of false premises.

Another critical characteristic of this commodity is its divisibility.

MD: If you know how to divide or multiply or add or subtract, you know everything you need to know about “real” money. With every other money you need exponentiation. With real money you don’t.

Unlike other commodities, it can be melted down and divided into smaller units without losing its intrinsic value, allowing for transactions of varying sizes.

MD: Maybe so… but money isn’t a commodity. Is this guy one of those Mises Monks?

This makes it more practical as a medium of exchange compared to goods that cannot be easily broken down.

MD: Alright. This is a good time to introduce the obvious proper unit for money. It is the “Hour Of Unskilled Labor” (HUL). It trades for the same size hole in the ground over all time and space. We’ve all traded our time for a HUL early in our lives. We baby sat. We mowed the lawn. We worked at McDonalds. They call it the minimum wage. People who recognize the “real money process”, can recognize a HUL. A HUL traded for the same size hole in the ground 3,000 years ago as it trades for now. And you can talk in 1/2 HULs if you want. Time can be more easily divided than any commodity can. And like HULs it trades for any fraction you want. It never changes over all time.

Additionally, it is fungible, meaning that each unit is identical to another unit of the same weight and purity. This interchangeability ensures that it can be exchanged without discrepancies in value, making it a highly efficient means of trade.

MD: This is obviously a Mises Monk. What attributes do we have now: (1) Durable; (2) Divisible; (3) Fungible;

It is also prized for its portability.

Despite being a physical commodity, it possesses a high value-to-weight ratio, allowing individuals and institutions to transport significant amounts of wealth in a compact and convenient form.

MD: “Real” money is just about record keeping. It’s value to weight ratio is perpetually “infinite”. The cost to transport it is perpetually “zero”. Can whatever this wonderful this guy is peddling… can it meet those metrics?

This portability, combined with its recognizability, reinforces its status as a widely accepted and trusted form of money.

MD: So is he claiming two more attributes: (4) value to weight ratio; and (5) recognizability. You know, I’m 80 years old. The only money I’ve ever experienced is the dollar, and its fractions and multiples. And when I was a kid, the paper version said “Silver Certificate” on it and you could demand silver for it… which nobody did. And in 1964, the coins had 90% silver in them. But in 1965 they quit putting silver in them… but they still traded for the same amount of gas. That proved beyond all doubt that people just viewed them as tokens of no intrinsic value at all. It’s obvious for all to see. She still hasn’t mentioned gold yet had she. Let me check. Nope. Still hasn’t mentioned it. But I know where this nonsense is going. It’s going where is always goes… and has never been in my lifetime or my dad’s lifetime.

Across cultures and throughout history, it has been universally acknowledged as a store of value, and its distinct appearance and unique properties make it difficult to counterfeit.

MD: Difficult to counterfeit? They can plate tungsten and unless you hit it with a tuning fork, you can’t tell the difference. Do these Mises Monks have just one essay to copy?

Beyond these qualities, it also holds scarcity, a fundamental attribute that has preserved its value over time.

MD: (6) Scarcity. Now why in the world would you want money to be scarce? You want it to be in free supply over all time and space. It is used for trade. You never want to inhibit trade. We’re up to 6 attributes and he still hasn’t mentioned his magic commodity… but we know it meets none of these 6 attributes.

Its supply is naturally limited by the physical constraints of extraction and production.

MD: You don’t want to limit supply. You want to maintain perfect supply/demand balance for money. Otherwise it doesn’t hold its value. It either becomes more valuable, which hurts one trader. Or it becomes less valuable, which hurts the other trader. The only time it works at all is for SBE… if anybody takes it these days. I guarantee you, WalMart doesn’t.

This inherent scarcity prevents artificial inflation and ensures that it maintains its purchasing power over extended periods.

MD: Prevents artificial inflation? When was Ft. Knox last audited. What was its value in 1973 when Nixon changed its value. It doesn’t work folks! And we still don’t even know what “it” is. Is anyone still reading this nonsense?

Lastly, its malleability adds to its utility, as it can be shaped into coins, bars, or intricate jewelry without losing its essential properties.

MD: (7) Malleability. Now really. How many shapes can a promise take on? You either keep it or you don’t. And the “real money process” (RMP) knows at all times. The instant you DEFAULT on your promise, the RMP is collecting INTEREST of like amount to make up for irresponsibility. Who pays the INTEREST. Well responsible traders don’t. They enjoy zero INTEREST load. So that leaves irresponsible traders.

This adaptability makes it highly versatile, further cementing its place as one of the most effective and enduring forms of money.

We are, of course, talking about gold.

MD: Finally the cat’s out of the bag. Why doesn’t silver qualify? Why doesn’t platinum? Why doesn’t gold plated tungsten? And if you have to wait for gold to become money, what do you trade with in the mean time? How do you get dirt turned into gold so you can pay the people that are digging it and turning it into gold?

And indeed, throughout history, gold has embodied all the qualities of strong money—it is scarce, durable, divisible, portable, and widely recognized.

MD: And in my lifetime, which is now 80 years, it has never been used as money… not once. In fact, I traded some of my dollars for gold with GoldMoney.com 20 years ago. To test their concept, I asked for my gold… and I got it in gold grams… less 10% import duty. How’s that for money? How’s that for holding value? And now they’re asking for all kinds of information they never asked me for when I made the trade of dollars for gold grams. And if I don’t give them the information, they won’t even let me see my records. And they’re right now in the process of making it more expensive to have my dollars (or what is in their vault) turned into the units of gold grams. Look them up. GoldMoney.com. See if you want to do business with them. Or go to your local pawn shop and see what you have to pay over spot price to get some. And it’s been that way my whole life, which is longer than the Mises Monk writing this article has been around, I guarantee that!

Its long-standing role in economic systems has led many to assert that it remains the ultimate form of money.

MD: The only ones I know asserting that are the Mises Monks… and they’re provably dead wrong.

At this point, a show of hands might reveal broad agreement with this perspective.

MD: No hands go up. Maybe some fists!

But before reaching a final conclusion, it is worth pausing and asking: Has history always functioned under a free-market system?

MD: When I bought my last Timex watch it did. It even said on the box… fair market price… and it was the same wherever you bought it. In fact, virtually everything I have bought was for the published priced. You don’t barter in the USA like you do in Mexico.

More importantly, has money always been determined by the free market, or has another force been at play?

MD: Ask Russia. USA isn’t a nice trading partner. They sanction their trading partners and take over their accounts. Right Russia?

Money as a State-Controlled Construct

A common assumption that must be accepted when using the definition of money found above, is that markets operate freely, driven by voluntary exchange and competition.

But does this match with historical reality?

Has history always been characterized by a Free Market? Or, more importantly, has the world ever been truly governed by Free Market principles?

MD: But that’s not because of the money.

These questions are essential, but they require us to look at the world as it is, not as we wish it to be. Which leads to a broader discussion about the nature of money itself.

If we assume that money is simply a commodity chosen by free market forces, then we must reconcile this assumption with historical evidence.

MD: Bad assumption. Money is “simply a promise to deliver spanning time and space”. It’s provable. Historical evidence won’t help us because governments have conned us over all time. The money-changers institute governments to do just that. I really intended to go through this whole thing… but I just can’t. How about you? I’m outa here!

And the simple fact is, there exists another perspective—one that challenges the traditional definition of money and forces us to reconsider whether money has ever been purely a market-driven phenomenon.

If history tells us anything, it is that the state has played a significant role in the shaping of history as a whole. The state has also played a significant role in the development of monetary systems.

So, if we are dealing with the world as it actually is, rather than how we want it to be, this simple fact cannot be ignored.

Throughout history, governments have issued various forms of fiat currency, not as a response to free market demand, but as a mechanism to facilitate trade, assert control, and support economic systems.

Ancient empires often minted coins made of base metals, stamping them with the images of rulers or state symbols, ensuring that their value was determined by decree rather than intrinsic worth.

These early monetary systems established a precedent where the state, rather than market forces, dictated what functioned as money.

During the Renaissance and beyond, paper banknotes emerged as a widespread monetary tool. Initially, these notes were backed by precious metals, reinforcing their legitimacy and trust.

However, over time, they gradually evolved into pure fiat money, entirely detached from any physical commodity.

This transformation allowed governments and central banks to exert greater control over monetary systems, as they were no longer constrained by finite reserves of gold or silver.

Colonial governments also played a significant role in monetary history, issuing promissory notes as a means of managing trade and economic activity.

These notes functioned as early forms of government-backed currency, representing an obligation rather than a tangible store of value.

As time progressed, fiat currencies became the dominant form of money, with modern states embracing national currencies such as the dollar, euro, and yen.

Today, fiat money exists in both physical and digital forms, serving as a testament to the continued evolution of state-sponsored monetary systems.

If we accept this historical reality, then we must ask: Is money truly a product of free markets, or has it always been shaped and defined by those in power?

Or put another way: Is money really the most marketable commodity that is chosen by the free-thinking individuals, or is it a powerful tool that is dictated by the King?

To answer these questions, it is first necessary to develop the skills needed to best understand one’s environment.

Situational Awareness

Situational Awareness is a fundamental skill that allows individuals to perceive, comprehend, and anticipate events in their surroundings, enabling them to make informed decisions and take effective action.

It consists of three essential components: first, the ability to perceive critical elements in the environment, such as people, objects, and unfolding events; second, the capacity to comprehend their meaning and potential impact; and third, the foresight to project future developments based on available information.

This skill is indispensable in high-stakes environments such as aviation, military operations, healthcare, and business, where the ability to recognize subtle cues and react accordingly can mean the difference between success and failure.

The same principle applies to portfolio allocation, where financial markets constantly shift, and a lack of awareness can lead to devastating losses.

Beyond professional fields, situational awareness plays a critical role in everyday life, enhancing personal safety, improving decision-making, and allowing individuals to navigate an ever-changing world effectively.

Without this skill, people risk being caught off guard, making poor choices, and suffering avoidable consequences.

Whether applied to personal security, financial decisions, or strategic thinking, situational awareness is a vital tool for optimizing outcomes in a world filled with uncertainty.

An example of applying situational awareness to our current topic at hand can be found in the below scenario.

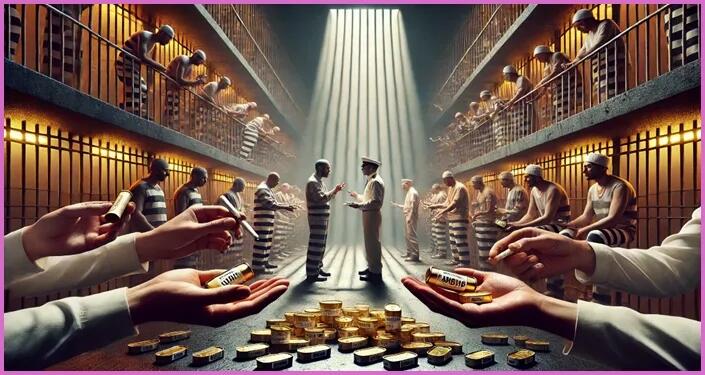

The Prison Economy

As noted above; to optimize one’s circumstances, it is necessary to fully understand the environment in which one operates.

This principle is starkly illustrated in the closed ecosystem of prison economies, where traditional monetary systems do not exist.

In such environments, inmates rely on alternative forms of currency, selecting goods that are durable, widely accepted, and easily exchangeable.

For example, cigarettes have historically functioned as an effective currency behind bars.

They are in high demand, easily divisible for small transactions, and widely recognized as a unit of exchange.

Cigarettes can be traded for food, services, or other necessities, creating a barter economy that mirrors traditional financial systems.

Similarly, cans of sardines have emerged as a valuable commodity in some prison settings.

Their non-perishable nature, combined with their nutritional value, makes them a reliable store of wealth that retains its usefulness over time.

In the absence of officially sanctioned money, these items take on the characteristics of a medium of exchange, a store of value, and a unit of account—the very principles that define money itself.

This informal economy within prisons serves as a microcosm of broader monetary systems, demonstrating that money is not defined by government decree alone, but by what people collectively recognize as having value.

The lessons from these controlled environments underscore the importance of adaptability, resourcefulness, and understanding economic forces, no matter where one operates.

Its also important to understand that while both cigarettes and sardines have become popular forms of money found in controlled environments, they have not become so solely due to the marketability of their intrinsic qualities.

Consider a scenario within a prison economy, where sardines are widely accepted as currency. In this system, they serve as a medium of exchange, a store of value, and a unit of account—fulfilling all the necessary functions of money.

However, what happens when an inmate is transferred to a different facility, where the power dynamics have changed?

In this new prison, the dominant figure—the one who holds the most influence—hates sardines but loves cigarettes.

He has declared, by fiat, that cigarettes are now the required form of payment.

In such an environment, it no longer matters that sardines once held monetary value. The rules have changed, and the new authority figure has dictated a new system.

In this situation, would it make sense to insist that sardines are still money?

Or would the prisoner be forced to adapt to the new standard, recognizing that money is not determined by intrinsic qualities alone, but rather by the power structures that enforce its use?

Would you take it upon yourself to try and convince the dominant figure that he is wrong to demand cigarettes and that he should rely on free market principles rather than his own wants and desires?

This example raises a critical question: If given the choice, would we prefer a market-based form of money, determined organically by free exchange, or a system where money is dictated by a central authority that holds power over the participants?

Most people would instinctively lean toward the former, believing that free markets should determine the best form of money.

And because they believe that free markets would be better, they then believe that that is how markets developed throughout history.

However, there is a problem with this perspective—one that is rarely acknowledged.

Despite its widespread acceptance in economic textbooks and theoretical models, there is little historical evidence that large-scale barter and free exchange ever formed the foundation of monetary systems.

The assumption that markets naturally produce money without some form of imposed structure does not align with much of the historical record.

This challenges the idea that money evolved as a product of free markets and forces us to reconsider whether its origins are more closely tied to power, authority, and enforced rules rather than voluntary exchange.

Most people assume money has always been determined by free market forces. But history tells a different story—one where power, control, and coercion have shaped financial systems in ways few ever stop to consider.

So if money isn’t what we think it is, what does that mean for everything else?

Debt, Power, and the Evolution of Money Systems

The conventional narrative about the origins of money suggests that it naturally evolved from barter systems, where individuals directly exchanged goods and services.

However, David Graeber, in his book Debt: The First 5,000 Years, challenges this assumption, arguing that there is little historical evidence to support the idea that barter was ever the primary foundation of economic systems.

Traditional economics textbooks often depict early societies as engaging in barter before money was introduced, but Graeber’s research suggests otherwise.

Instead, he argues that debt—not barter—was the foundation of economic exchange.

In ancient societies, trade was often based on credit systems, where individuals exchanged goods and services based on mutual trust and obligations rather than immediate physical payment.

These systems did not require money in the traditional sense but instead relied on social contracts and informal agreements.

Over time, these credit systems became formalized into structured debt, eventually leading to the emergence of money as an institutionalized means of settling obligations.

Graeber traces the evolution of debt through history, illustrating how it became deeply embedded in economic and political systems, often serving as a means of control rather than mere facilitation of trade.

He critiques the ways in which debt has been used to enforce social hierarchies, shaping power dynamics, and limiting individual autonomy.

By reframing the history of money around debt, Graeber sheds light on the underlying social mechanisms that govern economic systems—mechanisms that have long been overlooked or misunderstood.

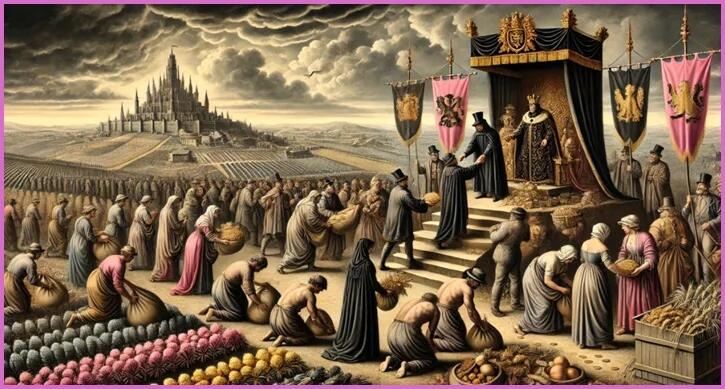

For example, it is well known that throughout history, rulers have exerted direct control over economic activity, using coercion, taxation, and structured debt to shape monetary systems.

In some cases, power was enforced through outright conscription, where the king would draft citizens into his army, demand their labor for infrastructure projects, or force them into servitude for state-building efforts.

There was little room for refusal—those who resisted often faced death or imprisonment.

In other cases, entire economies functioned under feudal systems, where peasants were forced to work the land, generating wealth that ultimately benefited the ruling class.

Under such systems, peasants were required to pay taxes “in kind,” meaning they surrendered a portion of their crops, livestock, or other goods directly to the monarchy.

After taxation, they were left with only what remained for their survival.

However, maintaining control through direct force has its limitations. It requires resources, effort, and an ever-present threat of violence.

A more efficient system would be one where control was maintained without constant enforcement—one where individuals voluntarily complied, believing they had agency in their economic decisions.

With that in mind, what if the king devised a system where, instead of demanding physical goods or direct labor, he issued a currency—a coin used to provision his kingdom?

What if, at the end of the season or the year, he required his citizens to pay back a portion of that currency as taxes?

Under this model, individuals would still be working to sustain the system, but instead of direct coercion, they would be compelled to participate in the economy to earn the issued currency.

The need to obtain coins to pay taxes would create demand for the currency itself, giving it value not because of intrinsic worth, but because it was the only way to satisfy obligations to the state.

In effect, this would achieve the same result as forced labor or direct taxation, but in a manner that was subtler, more efficient, and easier to manage. The system of control would still exist—but now, it would feel voluntary.

Before dismissing this idea as implausible, it is worth reflecting on the words of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who once observed: “None are more hopelessly enslaved than those who falsely believe they are free.”

Debt, Control, and the Nature of Power

The concept of debt as a mechanism of control is powerfully illustrated in the film The International, where Umberto Calvini, a leading global weapons manufacturer, explains to money laundering investigators why a major European bank is brokering Chinese small arms to third-world conflicts.

The investigators assume that the bank is simply profiting from war, but Calvini clarifies that the true objective is not to control the conflict itself, but to control the debt that war creates.

He states:

“The IBBC is a bank. Their objective isn’t to control the conflict, it’s to control the debt that the conflict produces.

You see, the real value of a conflict—the true value—is in the debt that it creates.

You control the debt, you control everything. You find this upsetting, yes? But this is the very essence of the banking industry, to make us all, whether we be nations or individuals, slaves to debt.”

Calvini’s words underscore a chilling reality: war (and debt) is not just about land, resources, or ideology—it is a financial instrument.

By ensuring that governments and individuals remain indebted, financial institutions and those who control them can exert long-term influence over entire nations.

This shifts the focus from direct control through physical force to economic subjugation through perpetual debt cycles.

The idea that control extends beyond war and finance is further explored in the film The Matrix, where Morpheus reveals to Neo the unsettling truth about the world he lives in.

Neo, like everyone else, believes he exists in a reality where he makes his own choices.

But Morpheus exposes this as a fabricated illusion, designed to keep people enslaved without them realizing it.

When Neo asks what the Matrix is, Morpheus explains:

“The Matrix is a computer-generated dream world, built to keep people under control in order to change a human being into…this.”

At that moment, Morpheus holds up a battery, revealing the horrifying truth—humanity itself has been reduced to a power source for an unseen system.

In the context of financial systems, this analogy is striking.

Just as the machines in The Matrix extract energy from humans, modern economic structures extract wealth, labor, and productivity from individuals, often without their conscious awareness.

Most people never question the system they are born into, just as Neo never questioned his world—until he was forced to confront an uncomfortable truth.

By drawing these connections, it becomes clear that debt, economic control, and systemic influence function in ways that extend far beyond what most people perceive.

The question then becomes: If the world we live in operates under a system we never consented to, and one that most don’t even understand, how much of our reality is truly our own?

The Monetary Matrix

After exploring various perspectives, we arrive back at the fundamental question: What is money?

But before we attempt to answer, consider this—are you ready to take the Red Pill?

What if, echoing the words of both Umberto Calvini in The International and Morpheus in The Matrix, money is not merely a tool for exchange, nor simply a product of free-market evolution?

What if money has never been neutral, but rather, it has always been a mechanism of control?

If this is the case, then money is not just an economic instrument—it is the original Matrix.

It has existed for as long as power structures have, shaping civilizations, ensuring compliance, and maintaining hierarchies thousands of years before modern financial systems were even conceived.

It did not emerge organically from free markets, but rather, it was implemented and imposed by those in power.

If this idea seems radical, consider the analogy: money is a government-created construct, built to keep people under control in the same way that the Matrix enslaved humanity—turning them into batteries for an unseen system.

Morpheus’ words about turning humans into a battery displays this concept perfectly.

But when Neo is confronted with this reality, his first reaction is horror and denial.

He recoils at the idea, rejecting it outright:

“I don’t believe it. It’s not possible.”

And perhaps, right now, you are having the same reaction.

Perhaps this notion seems too far-fetched—too extreme to be real.

And yet… can you be completely certain that it is wrong?

The challenge is not to accept or reject this idea outright. The challenge is to look at the world as it is, not as we want it to be.

If you can do that, then you must at least be willing to ask:

What if everything you thought you knew about money was an illusion?

But before we jump to a conclusion, let us take a closer look at some of the evidence. Evidence that we all have direct experience with.

The Evidence

From the moment we are born, we enter a controlled environment—one where registration is mandatory, where each individual is assigned an identification number.

This system is not referred to as a prison, but rather as a state or a country.

And yet, despite the different terminology, the structure bears an unsettling resemblance to an institution designed to manage and contain its inhabitants.

But unlike traditional prisons, this system is far more sophisticated. Here, you are not simply locked away—you are made to believe you are free.

You do not get to live in this system for free. There is a cost, a recurring obligation that must be met. They do not call these payments prison fees—they call them taxes.

Even though you are required to pay, you have little to no control over how the money is spent.

And to make matters worse, in order to obtain the money necessary to pay these taxes, you must first work within the system itself.

The economy is structured so that you must earn the state-sanctioned currency, which can then be used to pay the fees imposed on you.

There is no alternative. At least not one that does not involve the threat of imprisonment or violence.

But it does not stop there.

The system does not just demand your labor—it also encourages you to take on debt.

It presents you with shiny new products, new luxuries, new promises, enticing you to borrow more, ensuring that you remain tied to the system, dependent on its currency, and locked in a cycle that is nearly impossible to escape.

Unlike a physical prison, where the boundaries are visible, this system’s walls are invisible—and that is what makes them so effective.

You may believe you are free to move, but try leaving without the required documentation—a passport, a visa, or an approval.

Your movements are tracked, monitored, and restricted.

In some cases, certain “facilities”—whether by nation, regulation, or economic constraint—do not allow you to leave at all.

And yet, the most effective form of control is not force, but distraction.

The state provides news, entertainment, and endless engagement, ensuring that most people never even realize that the walls exist.

In fact, they are so skilled at this that the vast majority of individuals will never take a step back, never pause long enough to recognize the structure for what it truly is.

The Cognitive Dissonance of it all

Now, some of you may be thinking: This is not really what money is. This is just that MMT mumbo jumbo. And others may believe that if this were true, the system would have collapsed already.

But remember, inevitable does not mean imminent. Systems do not crumble overnight. They endure for decades, centuries, even millennia before their inherent flaws bring them to their inevitable collapse.

So, after examining the evidence—after considering the nature of the system we exist within—have you changed your mind at all?

Do you see the pattern, but simply hate what it implies?

Breaking Free

Understanding money as a mechanism of control does not mean outright rejecting the idea of free markets or market-based money.

Instead, it demands situational awareness—the ability to recognize and navigate the structures that shape financial systems, rather than blindly accepting them as immutable truths.

Free markets and commodity-based money may indeed be ideal, but reality tells a different story—one where monetary systems are largely centralized, manipulated, and designed to maintain power structures.

Acknowledging this reality is not about conceding defeat; it is about understanding the game you are playing so that you can engage with it on your own terms rather than being a passive participant in a system that was never built for your benefit.

The nature of money is inherently dualistic.

Sometimes, it is a market-chosen commodity, emerging organically from the free exchange of goods and services.

Other times, it is a state-imposed token, demanded by sovereign powers as the exclusive means to settle obligations like taxes.

And, in many instances, it is both at the same time—a hybrid of state control and market-driven value, existing within a framework that few ever stop to question.

None of this is meant to disparage free markets or the enduring role of gold.

On the contrary, history has shown time and time again that gold and sound money principles provide a more stable, trustworthy foundation for trade and wealth preservation.

If given the choice, most would prefer a system where markets, rather than governments, determine what functions as money.

But that is not the world we live in today.

To ignore this fact is to remain blind to the forces that shape global finance, leaving oneself vulnerable to the shifting tides of monetary policy, economic intervention, and centralized control.

Now more than ever, dogmatic beliefs about what money should be must not cloud our understanding of what money actually is.

In the years ahead, the ability to think critically, adapt, and remain aware of evolving financial realities will not just be valuable—it will likely be essential for financial survival.

Rather than clinging to an ideological framework that no longer aligns with reality, we must cultivate a mindset that allows us to see the world as it is, not as we wish it to be.

Toward Economic Democracy

Toward Economic Democracy by

by