Quotation of the Day…

… is from page 359 of the late Paul Heyne‘s insightful 1981 article “Measures of Wealth and Assumptions of Right: An Inquiry” as it is reprinted in the 2008 collection of Heyne’s writings, “Are Economists Basically Immoral?” and Other Essays on Economics, Ethics, and Religion (Geoffrey Brennan and A.M.C. Waterman, eds.) (footnote deleted):

MD: Notice how the Mises Monks never just cite an article and not its author. As in this case, there is always hyperbole … e.g. Paul Hayne’s “insightful” article. This is a Mises Monk marker.

Marxists have long complained that conventional economic analysis takes for granted the existing system of property rights. The charge is fundamentally correct.

Marxists have long complained that conventional economic analysis takes for granted the existing system of property rights. The charge is fundamentally correct.

MD: Let’s see if he exposes the alternative to this? Hint: No he doesn’t.

Am I likely to paint a house that isn’t mine? Am I likely to build a house on property that isn’t mine?

Offers to supply goods and efforts to purchase goods always depend upon people’s expectations of what they can and may do under specific contemplated circumstances. What a person may do expresses, in the broadest sense, that person’s property rights.

MD: Remember … a right is a defended claim. Here we have an implicit claim and no defense suggested. Do we really think we have a right being talked about here?

In order to predict, explain, or even talk intelligibly about those patterns and instances of social interaction that we call “the economy,” we must begin with people’s expectations, that is, their property rights.

MD: Why do they see the economy as a “social” interaction? If everything was an automat, would it still be a social economy? An economy is about trade. There is nothing social about trade in most cases. The purpose of advertising is to socialize it … but that’s not an attribute … it’s just a tactic

DBx: To avoid possible misunderstanding, I would have slightly reworded the final sentence of this quotation to read: “In order to predict, explain, or even talk intelligibly about those patterns and instances of social interaction that we call “the economy,” we must begin with people’s legitimate expectations – namely, those expectations that are widely shared and agreed to throughout the community – that is, their property rights.”

MD: Ah … now you talk about a great Misesian improvement. Add more words and say even less.

Heyne’s point is profound and important. Obviously, we cannot possibly distinguish illegitimate coercion against others from the legitimate exercise or defense of one’s rights until we know in sufficient detail the property-rights arrangement.

MD: Which will be found in a spaghetti of conflicting laws, rather than a simple statement of principle … like the golden rule.

If I break the window of a house at 123 Elm St. and then enter, you cannot know from this physical act if I am burgling the house (and hence, violating someone’s property right) or entering the house with the permission of the homeowner (namely, in this example, myself who locked myself out of this house that I own).

What is less obvious, but no less important, is the fact that property rights boil down to shared expectations.

MD: And of course “principles” are shared expectations. Laws are not.

In modern America (as in most modern societies) ownership of a house includes the widely shared expectation that in all but extreme circumstances – for example, when the house is engulfed in fire – the right to decide who may enter the house is reserved to the homeowner. Ultimately, this right rests on widely shared expectations. If I, a modern American, move to some community in which the widely shared expectation is that anyone who wishes may enter unannounced into any house in that community, with or without the permission of the owner or occupants, and by whatever means, then no right of mine is violated if some stranger breaks into my house.

MD: And can we picture any collection of people who would see this behavior as adhering to the golden rule? Actually we can. Most utopian societal communal failures see things this way.

Expectations, being what they are, can be affected by the formal legal and legislative codes, but expectations can also diverge from these codes.

MD: Which makes those codes pretty worthless, doesn’t it … especially when we get 40,000+ new ones every year.

(An example of such a divergence is the fact that in some U.S. states – I think, for instance, in Massachusetts – it remains an ‘on-the-books’ criminal offense for two adults who aren’t married to each other to have consensual sex with each other. Yet community expectations now no longer regard such activities to be unlawful.) Expectations change more frequently (especially in open societies) than does the formal law and the legislative codes, and expectations are always more nuanced and ‘granular’ than articulated legal rules or legislative commands can possibly be.

MD: But if were about principles rather than laws, the golden rule principle would easily address this … i.e. it’s only the business of the two people involved.

At bottom, a society’s laws are its widely shared expectations about how individuals may and may not act toward each others’ persons and toward the material things, as well as the symbols and markers, that individuals possess and use as they conduct their affairs both individually and in groups.

MD: A misstatement. Its principles, not its laws, are the widely shared expectations. Its laws are a hopelessly flawed attempt to nail down the jello which is those principles. As I’ve stated before, it would take an unlimited number of laws to nail down the principle of the golden rule.

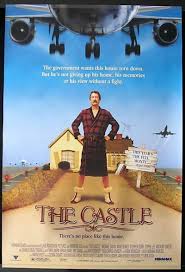

(By the way, do watch the 1997 movie, The Castle.)